Bill Rock Art

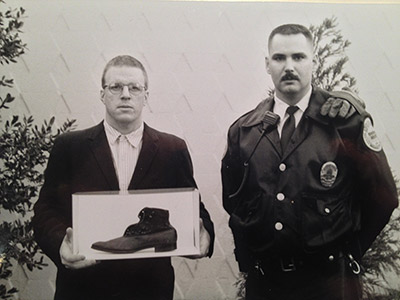

Footwear of the German Expressionists:

The Driving Force Behind the Angst

In the summer of 1995, I was invited to exhibit work at the Egon von Kameke Gallery in Potsdam, Germany along with other artists from The Emerging Collector in New York. During my stay in Potsam, I did a performance piece with Juan Carlos de Castro, a Berlin based musician. During my first meeting with Juan, we talked about our plans for the piece while he looked at several drawings I was exhibiting in the gallery. He studied two of the drawings at length and when the gallery owner commented on them, Juan pointed to the high heeled shoes on one of the figures and said 'das shoe de Kirchner'. I thought he was commenting on the drawing style being in the expressionist vein, similar to that of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, when in fact, he was speaking of this type of shoe being like the Kirchner shoe. He explained to me that not only did Kirchner draw and paint shoes of this type but he wore them as well. I was a little surprised about Juan's knowledge of such an obscure piece of information until he revealed that he had seen the shoe in an exhibit at The National Museum of Historical Artifacts in Dusseldorf some years ago. The exhibit had been called KUNST FASHION and featured clothing of German artists and designers from 1900 to 1980. The exhibit focused on the comparative characteristics between the artists and designers created and what they wore themselves.

In the summer of 1995, I was invited to exhibit work at the Egon von Kameke Gallery in Potsdam, Germany along with other artists from The Emerging Collector in New York. During my stay in Potsam, I did a performance piece with Juan Carlos de Castro, a Berlin based musician. During my first meeting with Juan, we talked about our plans for the piece while he looked at several drawings I was exhibiting in the gallery. He studied two of the drawings at length and when the gallery owner commented on them, Juan pointed to the high heeled shoes on one of the figures and said 'das shoe de Kirchner'. I thought he was commenting on the drawing style being in the expressionist vein, similar to that of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, when in fact, he was speaking of this type of shoe being like the Kirchner shoe. He explained to me that not only did Kirchner draw and paint shoes of this type but he wore them as well. I was a little surprised about Juan's knowledge of such an obscure piece of information until he revealed that he had seen the shoe in an exhibit at The National Museum of Historical Artifacts in Dusseldorf some years ago. The exhibit had been called KUNST FASHION and featured clothing of German artists and designers from 1900 to 1980. The exhibit focused on the comparative characteristics between the artists and designers created and what they wore themselves.

Two days later I was visiting The National Museum of Art in Berlin and wondered if they had any information on the Kunst Fashion show. The Exhibitions Librarian, Annadora Kleinfelder told me that the show had traveled to four museums including Berlin's National Museum of History and that one of their former conservators, a Thomas Schuler, had been one of the main advisors for the exhibition. He was instrumental in acquiring most of the artist-related artifacts including Kirchner's shoe. She told me that he had retired from the museum and was now a private conservator still living nearby. I then asked where I could see the shoe. Ms. Kleinfelder said she had no idea but I should contact the National Museum of History. I phoned. The museum was closed for three weeks for renovation. Ms. Kleinfelder could have Thomas Shuler contact me if desired.

Mr. Shuler telephoned my hotel the next day and I met with him at his small, second floor shop near downtown Berlin. After exchanging pleasantries, I explained my interest in the Kunst Fashion Show. Mr. Shuler advised me to find the catalog in the library at the Museum of History. I explained that I really just wanted to see the shoe, the museum was closed and I was leaving in a week. He told me that the shoes(there were actually three! One Kirchner, and a pair alleged to be from George Grosz) had been auctioned off with the rest of the Kunst Fashion Exhibit to raise money for new acquisitions coming from the East following reunification. The auction, titled KUNST LOAN had targeted wealthy art patrons and corporations in Berlin to bid on artifacts while deducting taxes. Deutsche Bank had the Grosz shoes and The Jon Himmelman Estate had Kirchner's shoe.

Schuler told me that the Himmelman Family were well-known patrons of the Berlin Museum of Art. But their wealth was gained under questionable circumstances between WWI and WWII. He wasn't specific about what these circumstances were, but stated that the patriarch of the family, Jon Himmelman had been a studio assistant for Kirchner and other artists of Die Brucke when they had a group studio in Dresden and that he 'profited from their deaths'.

On my second visit to his shop, after an embarrassing amount of cajoling, I learned that Schuler had a personal history with the Himmelman family. In 1959, Schuler was working as an associate conservator for the National Academy of Arts in Berlin. The newly formed academy's mission was to reassemble the art catalog for the national archive following WWII. Schuler learned through art circles that Jon Himmelman, who died in 1958, had left behind a number of notable items from Die Brucke days in Dresden. Among these were rumoured to be photographs of early German expressionist works. Schuler, who had been positioning himself as the archive's authority on Die Brucke contacted Himmelman's son Kurt and arranged a meeting to discuss possible donations or loans to the National Archive. At this meeting Kurt Himmelman presented Schuler with a trunk which he said contained the remains of his father's entire collection from Dresden. The trunk contained four unsigned pencil sketches of questionable quality, some theatre costumes, several letters and a shoe. Any photos had been given to an uncle in Munich who had always supported Jon Himmelman's artistic pursuits. Schuler accepted the trunk and placed it in storage.

Schuler contacted the family five years later after seeing their name on a list of potential patrons of the archive. Again, Kurt Himmelman referred Schuler to the mysterious uncle in Munich. Schuler, at his own expense, traveled to Munich in the summer of 1967. After 2 days searching through city records, he was at the doorstep of the uncle and the much-rumored Die Brucke photo collection.

There he met Jon Himmelman's niece, Anna Himmelman Martinson, daughter of the mystery uncle who, he now learned had died seven years earlier at the age of seventy-one. Schuler's quest was not in vain. After explaining his visit and the background of his search, Anna presented him with six photographs from the Jon Himmelman trunk(now in archive storage). The photos, she explained were the only ones given to her father along with two Kirchner woodcuts. The woodcuts were to stay in the family collection but the photos could go to the National Archive. Schuler left Munich with mixed feelings. Three of the photos were of costumed members of the Die Brucke during a social event. Two of the costumes matched those from the trunk which now became a valuble historical find for Schuler. Two of the remaining photos were out of focus, and the last was a gimmicky studio shot of Kirchner and Himmelman preparing an exhibition. But what bothered Schuler most was the fact that when he contacted Kurt Himmelman for the second time, back in 1964, he was again given the Munich uncle as a contact for any museum donations. But in 1964, the uncle had already been dead for three years. Schuler was greatly insulted at being lied to and concluded that the younger Himmelman probably  sold off the bulk of the elusive photographs to private collectors for his own gain. This would be consistent with the previous rumors concerning his father and his curious rise in financial well-being in the late 1920's. Enough so that he could move his entire family to a villa outside Geneva Switzerland for a period of fourteen years(1931-1946). The vague story (according to Schuler) centered around Jon Himmelman secretly staeling paintings from members of Die Brucke, notably Mueller, Heckel and Kirchner while he was cleaning the studio at night. This was rumored to have gone on for some four years, between 1909 and 1913. He was to have sold these during the next thirty years following the deaths of each of the artists.

sold off the bulk of the elusive photographs to private collectors for his own gain. This would be consistent with the previous rumors concerning his father and his curious rise in financial well-being in the late 1920's. Enough so that he could move his entire family to a villa outside Geneva Switzerland for a period of fourteen years(1931-1946). The vague story (according to Schuler) centered around Jon Himmelman secretly staeling paintings from members of Die Brucke, notably Mueller, Heckel and Kirchner while he was cleaning the studio at night. This was rumored to have gone on for some four years, between 1909 and 1913. He was to have sold these during the next thirty years following the deaths of each of the artists.

After what seemed like more than a cordial moment of silence, and becoming slightly anxious about the time, I returned to my original inquiry; where can I see the shoe? Schuler seemed annoyed at my impatience and said that I should call on Anna Himmelman, 'she has everything'. I mentioned that my travel would not take me to Munich. Schuler noted that I could find her in an Elderhaus in Berlin. The address was in the telephone directory.